Lamborghini Countach v Ferrari Testarossa

The world has changed a lot since the mid-1980s, more than those of us of a certain age would like to think. Roads are more clogged, speed limits are lower and more numerous, much of the population adopts a higher moral tone when fast and thirsty cars are involved. All of which alters the way we see cars such as the Lamborghini Countach and the Ferrari Testarossa, the twin peaks (limited-run hypercars excepted) of 1980s supercardom.

Then there’s the meeting-the-film-star element. Obviously we were awestruck back then if we saw and heard one or other of these red (and they usually were red) monsters. Objectivity would not apply; if we read in a road test that the windscreen misted up or the window winder interfered with the driver’s knee, we’d be irritated. So what, we would think. Just tell me how fast it goes, what it sounds like and how it makes you feel. And meanwhile, I’ll just carry on ogling the poster.

Was there an element of the emperor’s new clothes here? Was it that no-one dared to be hard-headed and truly objective? Would anyone have listened if a pundit had dared to go against the flow?

Twenty-five years on, it’s an extraordinary experience to get up close to these cars again. Suddenly we can see them for what they really are, the hype having long retreated to leave just the metal, glass, leather, plastic and rubber.

Even the numbers have lost their ability to shock. The arrival of the 200mph supercars – F40, XJ220 – saw to that, and nowadays a five-second 0-60mph time is regularly achieved by cars that look almost normal. But such pace was extraordinary back in the 1980s, as were top speeds that in both cases topped 180mph. On its launch, the quattrovalvole version of the Countach was the world’s fastest production car.

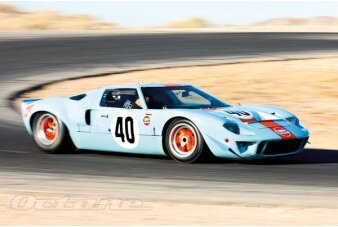

As supercars have become ever more aggressive and outrageous, what once seemed fascinatingly outlandish can soften almost to normality with the passage of time. This, as you can see, has absolutely not happened with the Lamborghini. Curiously, its shape – at least, as represented here – has turned out to be almost ageless. Lamborghini could launch it now with very few tweaks: bigger, non-retracting headlights perhaps, rounder front corners, even bigger wheels and lower-profile tires. (And a completely new interior, but we’ll get to that.)

Some say the original, 1970s Countach is the purer archetype, with its smoother surfaces and the lack of wheelarch extensions and rear air scoops, but that car is visually a part of its era. With the brutal addenda, however, the Lamborghini became so obviously functional that the fashion element of styling practically vanishes from view – and with it, an obvious slot in history. But there were limits to how much brutalization the shape could take and still retain its integrity.

The huge, arrowhead rear wing looked outrageous,

but those venturing towards the gummed edge of the Countach’s speed envelope reported that it really did improve stability, even if the extra drag ultimately slowed it down. So we could let that one pass. Not the striated sill extensions of the final cars though, which just looked like

a cheap, tacked-on imitation of the Lambo’s greatest adversary’s flanks. Far better to see the smooth, tucked-under curve of the sill itself.

That’s the way the car you see here is presented, and it also lacks the wing. So it’s the perfect visual blend of purity and muscularity, promising monstrous power and a battle of wills. Can a boxer-engined Ferrari compete with that?

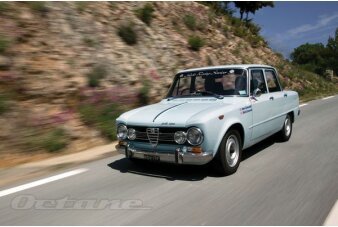

Straightaway you can sense the different approach. The Countach battles with the air and the road, the Testarossa tries to co-operate with them. The whole look of the Ferrari suggests an effortless flow through the air, the join between bumper and nose leading to a swage that sweeps upwards to become a broad shoulder atop the rear wheels. Below is the TR’s most striking styling feature, the stack of five strakes, which grows out of the door to guard hefty air scoops between door and rear wheel. These feed the radiators, whose rear-side positioning is the reason why the Testarossa is so wide.

Or so we thought at the time, yet actually the Testarossa is just half an inch broader than today’s 599 and FF, and actually an inch narrower than the Countach thanks to

the latter’s bulging rear arches. It just looks wider because the slab body sides are pulled right out beyond the wheels. There’s no rear spoiler here, and the glass area is wider and deeper all round. It’s a crucial difference.

I drive the Ferrari first, an ultra-low-mileage example (just 13,000 recorded) lent by obliging and trusting specialist Foskers, whose Brands Hatch emporium is filled with fine examples of redness through the ages (the Testarossa in these pictures, from Cheshire Classic Cars reads just 626 on the odometer – it even has its original fitted luggage in the passenger footwell). It’s red, of course. The Goodyear tires are old and hard, possibly near-original, and I’m struck by what today seems the cushioning depth of their sidewalls: a 50 profile was racy back then but every sport-pack family car has them now.

It does look a big, unwieldy thing, the impression of width emphasised from the rear by the black strakes spreading right across the tail panel. More black air-extraction strakes surround the bulge in the engine cover set between the buttresses aft of the vertical rear window. Why a bulge? Isn’t the engine a low, compact flat-12? It is, of course, but it sits on top of the gearbox, which it drives via spur gears, a bit like an original Mini’s arrangement except that, here, the gearbox has its own oil supply – an excessive-sounding 9.5 liters of it. So despite the engine’s flatness, the complete powertrain is bulky and has a higher center of gravity than you might have expected.

Now to get inside. The door opening is long and low, the door itself is unusually thick at its rear edge and shows those strakes in intriguing cross-section. Ingress is easy past the wide sill, the drop-down handbrake and the two chromed handles to release hood and engine cover, and once installed in the multi-adjustable driving seat you discover a panoramic view forward and surprising airiness behind. Angled junctions and close-quarters manoeuvring hold no fear in the Testarossa.

To your left, between the seats, is a plateau of plastic buttons that looked very high-tech in the 1980s but seems dirt-attractingly dated now. Ahead of it are the odometer and trip meter, far away from the rather Fiat-like main dials beyond the three-spoke Momo steering wheel, while further Fiatness manifests itself in the stalks on the steering column. I don’t think I’d have been impressed had I just paid the £62,666 the Testarossa cost new in 1985.

However, salvation is at hand. Left hand, to be specific, towards which is cranked a slim, chrome gearlever with a shiny black spherical knob. The lever sprouts from the open gate that was a standard Ferrari fearture before paddleshifts arrived to make everyone think he or she is a Formula 1 driver. Now, time to tame the bulky beast with its 390bhp awaiting the opening of the stable door. That was a stupendous amount of power for the time, beaten only by the saucy, meaty rival from Sant’Agata Bolognese.

I turn the ignition key; no gimmicky, cod-retro start button here. Twelve compressions flow into one resistance, free of starter pulsations, and… what? The engine erupts but no windows break and the earth doesn’t move. The bass burble is deep but smooth, the Bosch KE-jetronic fuel injection and Marelli Microplex ignition keep manners neat and temperament sweet. This was always intended

to be the civilised supercar in a way that the 512BB predecessor did not quite manage, and so far the brief seems to have been kept.

Into gear. Some springy obstinacy here, but the gearbox oil is cold so things will improve because that’s how Ferraris always were. Weren’t they?

Off we move towards fast A-roads, the width surprisingly unnoticed (just remember those broad rear haunches, which cut off the lower parts of both double-stalked door mirrors’ fields of view), the steering surprisingly slow-witted. It’s a non-powered system, because back then only Honda thought a mid-engined supercar should save its driver’s shoulders, but it’s light enough on the move. I just need to re-programme my movements after driving to Foskers in a wrist-flicking Eunos Roadster (the same age as this Ferrari, incidentally).

Well, this all feels very benign if a touch over-specified for the ambling experienced so far. Second gear is truly obstructive, though, just as Ferrari legend says it should

be. Why it needs to be so has never been clear. Was it a deliberate propagation of intrigue, easier to sustain than actually fixing the problem?

Now to explore the deeper reaches of the accelerator pedal’s travel. Below 3,000 rpm the engine is gentle, docile, torquey enough to be stroked along. From 3,000 there’s more gusto, more bite and you sense an awakening of the beast. Beyond 4000rpm the note hardens, throats open and the vocals take on a touch of Bryn Terfel in full Jubilee-concert potency. The engine will spin beyond 7000rpm with ease, passing the power peak at 6,300 rpm en route, and though very smooth it always retains the slight rasp that betrays the racing-engine influence.

Now, keep the engine in its rumbustious vocal zone, point the Ferrari along some bendy, undulating lanes and suddenly it becomes a car I did not quite expect. The gearbox remains obstreperous but the helping foot of a double-declutch can sometimes soothe it, and more significant is that, with meaningful loads applied to the front wheels, the steering sharpens to become apparently quicker than it really is while telegraphing all you need to know about grip and loadings. There’s a decent ride quality here too, so long as you can avoid the worst examples of modern-day road neglect.

I’m having a great time here, the Ferrari proving agile and responsive as though 20% smaller than it is. I’ve warmed to this car, its easy usability and its accessible thrust, and despite the aged tires I haven’t encountered any of the tail-loosing tripwires from which a really

quickly driven Testarossa reportedly suffered.

Fact is, though, I also haven’t encountered a bend long, clear or fast enough, and while you can normally divine a car’s handling characteristics pretty accurately long before you’re launched into a hedge, I have a hunch that physics might do the TR no favours on the limit. Contemporary road tests talked of an edginess at speed on fast bends, with steering inputs having exaggerated, destabilising effects. That’s the high-mounted engine’s mass shifting unhelpfully, I suspect.

From slightly awkward, clunky dinosaur the Ferrari has metamorphosed into a promising driving machine by the time we arrive at Kent High Performance Cars, where we meet the Lamborghini and its trusting owner Mark Hart. We shall now repeat our rural route and my 1980s fantasy re-enactment will be complete.

It starts with high drama. Specifically, the opening of the doors, ‘scissor’ doors which hinge upwards from their front edges, giving the Lamborghini the look of a giant ladybird at take-off. So steep is the tumblehome of the doors’ windows that there would be nowhere for a full door glass to retract into, even without a NACA duct in the way, spearing its arrowhead along the flank. So just the bottom half of the door glass winds down, manually and not very far. The greenhouse effect, I believe they call it.

Surprisingly, the Countach is a foot shorter than the Testarossa. It’s also about 160kg lighter, even though both cars share similar tubular-chassis construction. Having a V12 rather than a flat-12, albeit still with 48 valves and a capacity around five liters (actually 5167cc against the Ferrari’s 4942), means the Countach can’t place its gearbox beneath the engine.

True, its Miura ancestor did, but here the engine is longitudinal rather than transverse and the gearbox sits ahead of it, occupying the hefty tunnel between the seats. Drive then passes by a shaft through the engine’s sump to the differential aft of the engine. This arrangement allows a small and hot luggage boot in the tail but deprives the cockpit of storage behind the seats.

Being a quattrovalvole, this Countach has a hump above the engine rather larger than the Ferrari’s to accommodate the six Weber 44DCNF carburettors that sit aromatically

on top, instead of out to the sides as in earlier Lamborghini V12s. You see this hump in the rear-view mirror as soon as you’ve threaded your way over the high, wide sill into the snug-looking bucket seat. It’s all very race car.

The cabin is liberally covered in leather but unfortunately that doesn’t make it either luxurious or sophisticated. The quality, fit and finish are breathtakingly poor for a car costing £66,631 new, but people didn’t seem to mind much at the time. Not with 455bhp of gurgling, blattering, shrieking V12 to divert their attention.

I pull the door down, hard because it’s the only way

to guarantee a successful latching. Then I realise I can

see very little behind, thanks to that engine-hump and

the huge air-scoops that render the miniature door mirrors close to useless. If there’s a blue flashing light behind, I could be in blissful ignorance for too long to

help my case in any subsequent encounter with the

forces of darkness.

I can’t get the seat quite far forward enough to depress the heavy, long-travel clutch comfortably, but were I able to do so the other pedals would then be too near. So: brace my back, heave on the clutch, feel the seatbelt clasp dig into my left kidney and cajole the gearlever, through another open gate, into first.

This is one physical car. The steering is very heavy at low speeds, which goes well with the efforts required by the other major controls. The suspension rumbles and fidgets on its solid joints, although the ride is actually smoother than it sounds. Like the Testarossa, the Countach has double spring/damper units for each rear wheel.

I’m sitting low, much lower than in the Ferrari, and I really can’t see as much as I’d like given the steering’s

very obvious looseness at low speeds and what happens when the accelerator is squeezed. The intakes snort and the exhausts bellow, the ensemble going via a low-revs flat-spot, through a gutteral mid-range reminiscent of a Rolls-Royce Merlin’s rumble, to reach a tearing climax as the 455bhp meet their 7000rpm rendezvous on the

power curve.

The Testarossa feels very quick, but it can’t match the sheer explosiveness of the Countach’s getaway, as particularly well demonstrated on one opportunistic exit from a side road. And all the while the transmission

clanks and chatters by my left thigh, and then it rains and

I wonder what will become of the Lamborghini and me

as I peer past the pantograph wiper and experiment with more power. Will power and the lubricating effect of

water prove too much for the rear tires, even with their mighty 345/35 section?

Actually it proves surprisingly grippy, a grip felt partly through steering whose character changes dramatically with increasing pace. Now it’s Ferrari-precise, if meatier, enough so to wash away the fear of inaccurate placement and let me start to enjoy the Lamborghini. Like the Ferrari it really needs bigger roads and fewer other vehicles to share it with, but when congestion and constriction thwart the flow the frustration is all the greater because you still have to expend such effort merely to keep the Countach moving. Could I live with such a demanding motor car?

That question is answered as soon as I get back into the Ferrari, which suddenly seems a model of painstaking production development and driver-friendly ease of use, including a gearchange that now feels as easy as a

Honda’s as the relative temporarily trumps the absolute. Driving it back to Foskers, muscles still memorising the workout they have just endured in its rival, I realise I have become very taken with the Testarossa but I am content

for the Countach to remain a once-only experience. The Lamborghini has a mystique around it, perpetuated perhaps by people who haven’t actually driven one, but as a car to be enjoyed for driving on real roads it seems, engine apart, to miss the point.

Yes, sometimes it’s better not to meet the film star. You never know how it will turn out face-to-face.

Thanks to Cheshire Classic Cars (where the Testarossa is for

sale), www.cheshireclassiccars.co.uk; Foskers, www.foskers.com; Lamborghini Wycombe, www.lamborghiniservice.co.uk; Kent High Performance Cars (The Ferrari Centre), www.khpc.co.uk; and the Countach owners Mark and Paul Hart.

1989 Ferrari Testarossa

ENGINE 4942cc flat-12, DOHC per bank, 48 valves, one Bosch KE-jetronic injection system per bank

POWER 390bhp @ 6,300 rpm

TORQUE 361lb ft @ 4,500 rpm

TRANSMISSION Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

STEERING Rack and pinion

SUSPENSION Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: double wishbones, paired coil springs and telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

BRAKES Vented discs

WEIGHT 1641kg

PERFORMANCE Top speed 180mph. 0-60mph 5.8sec

1988 Lamborghini Countach QV

ENGINE 5167cc V12, DOHC per bank, 48 valves, six Weber 44 DCNF carburettors

POWER 455bhp @ 7,000 rpm

TORQUE 370lb ft @ 5,200 rpm

TRANSMISSION Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

STEERING Rack and pinion

SUSPENSION Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: double wishbones,

trailing links, paired coil springs and telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

BRAKES Vented discs

WEIGHT 1480kg

PERFORMANCE Top speed 183mph. 0-60mph 5.0sec

Published Dec 7th, 2015