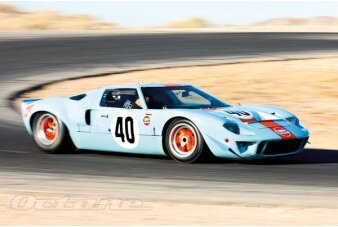

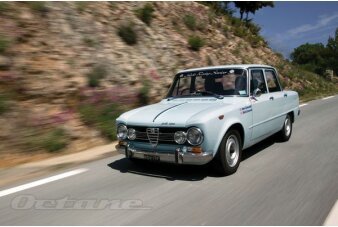

Classic Camshafts 101

Modern camshafts don’t wear out. This may be a revelation to you, dredging up memories of cars fitted with Ford Pinto engines – Buick V8s, just two of many engines that would delobe themselves at the earliest opportunity.

Given the right circumstances, a modern replacement camshaft in a classic engine is also likely to last way past expectations. This is phenomenal when you consider the stresses on a typical camshaft, spinning at half engine speed (so 3000rpm or more), lifting each valve up to 60 times a second. And all with just the thinnest film of oil as lubrication.

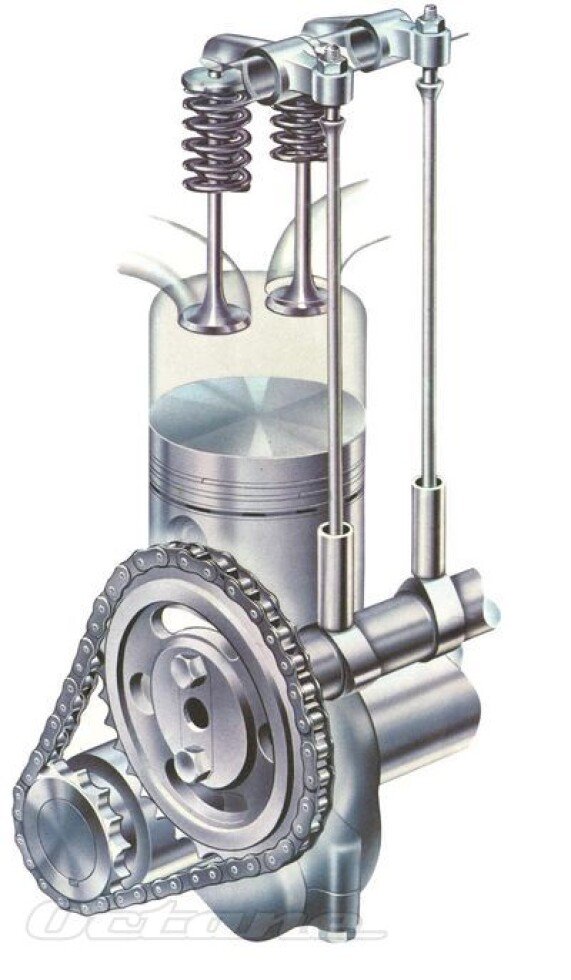

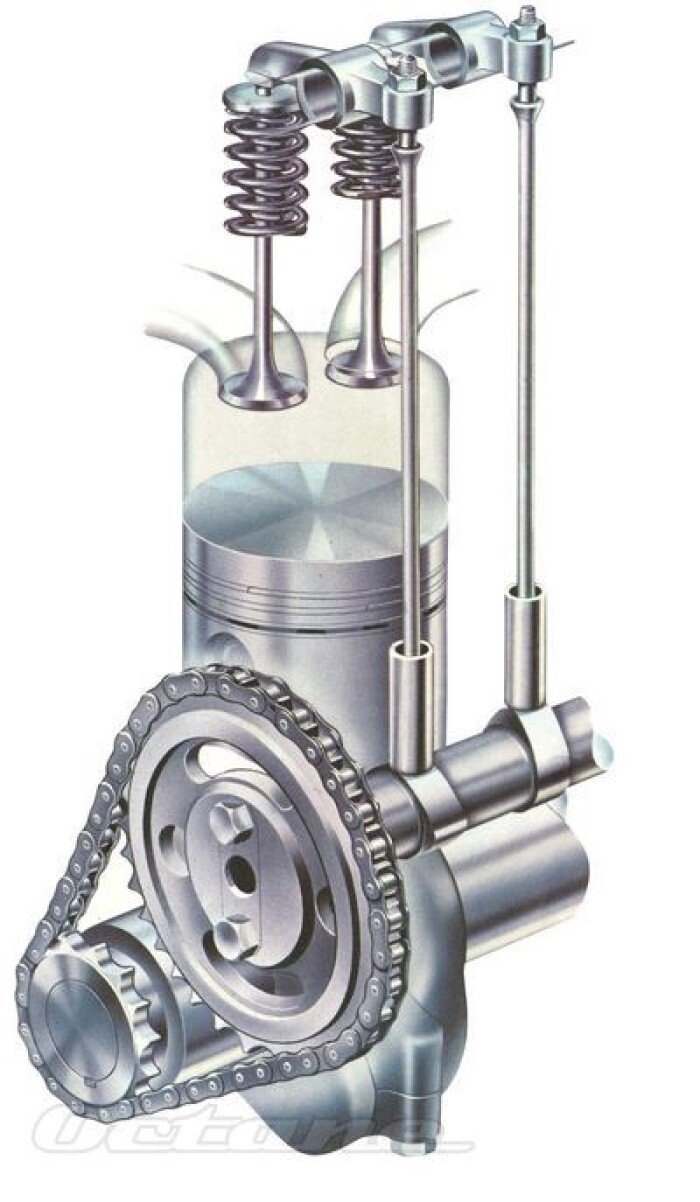

A camshaft has lobes – vaguely egg-shaped in profile – that are used to push the valves open. Thought of with the peak of the ‘egg’ at the top, the bottom of the cam is the base circle, the sides are the opening and closing ramps, and the top is the nose circle. Between ramps and nose are the opening and closing flanks.

A rocker arm or cam follower (often referred to as a tappet) will be pushed up or down by the camshaft but should only be in contact with the camshaft on the flanks and nose, not on the base circle. It’s crucial that there’s clearance between rocker/follower and the base circle to ensure lubrication – this valve clearance is usually set by screw-and-locknut or by shims. Too much clearance and the engine will be noisy and the valves won’t open far enough.

Some camshafts run at the top of the engine (overhead camshaft), others are buried further into the depths, opening the inlet and exhaust valves via pushrods and rockers (overhead valve). In sidevalve engines, the camshaft will be in the depths but valves may operate directly on them, opening upwards alongside the cylinders rather than above them.

Most modern overhead-cam engines use a toothed fibre-reinforced rubber belt to drive the camshaft, but before the 1970s a single-width or duplex chain was generally used – noisier and more expensive than a belt but less prone to breakage. Or sometimes the camshaft is gear-driven, which is efficient and maintains perfect cam timing but can also be noisy.

But the crucial bit to us is what goes wrong, and how to stop that happening. And, of course, how changing a cam can release more power and torque.

The secret to prolonging camshaft life is regular oil changes. There’s little else that can be done to preserve your camshaft except to ensure that an engine that’s been laid up for a while receives a healthy dose of engine oil on the lobes before start-up – by removing the cam (or rocker) cover(s) and squirting oil on to the cam lobes or down the pushrod holes.

Unfortunately, some camshafts are going to wear out, however well you treat them. The best tended to be produced in forged steel (MGB and Mini camshafts for example), while others (like the Ford crossflow) used cast-steel camshafts that were induction hardened by using a coil of wire around each lobe to heat the metal, then immersing the camshaft in oil. But the hardening can wear through.

By the 1970s, camshafts began to be chill-cast by having a gas introduced into the mould at the casting stage, the gas reacting with the hot metal and hardening it. Most modern camshafts are chill-cast, and they don’t tend to wear out.

Fortunately, there’s no camshaft that can’t be replaced. Popular classics are easy: taking

Comp Cams as an example, it’s possible to buy brand new camshafts that are ground to your specification from ‘semi-finished’ blanks held in stock – new cams on which the lobes haven’t yet been completed.

Another step up the ladder and we get into the engines for which it’s possible to buy camshafts made from steel billet that can be ground to shape.

But if you have something rarer, a camshaft

can still be produced, often from original specifications that a company such as Comp will hold in its archives, or from measurements of the original camshaft.

What’s crucial is that new cam followers are always fitted with the new camshaft, and that those followers are high quality; they contain high levels of chromium, which is expensive, so some followers coming in from the Far East are too low in chromium content.

It’s also important to use proper cam lube on a new camshaft, and to ensure that the lube is topped up before first start-up if the engine has taken a while to put together. It’s also important not to allow a new engine to idle slowly.

Of course if you’re going to replace a camshaft, there’s the obvious temptation to upgrade to a more efficient or performance-orientated specification.

Competition engines will use even wilder camshafts but they’re no use without appropriately comprehensive cylinder head, fuel system, ignition and exhaust modifications, and driveability will be compromised.

Many fast road camshafts are relatively cheap because they’re produced by regrinding an old camshaft, altering the profile by reducing the base circle diameter (which would never have been hardened, so no need to worry about breaking through the hardening).

All camshafts are ground relative to the original timing keyway, so there’s rarely any need to adjust the cam timing except to deliberately tweak the engine characteristics – vernier cam pulleys and offset Woodruff keys are available for some engines for that purpose.

What is important is to ensure that valve springs are compatible with new camshafts – extra valve lift can cause the springs to go coilbound – and that there’s no chance of valves hitting pistons. Camshaft suppliers will be able to advise you on that.

But what’s really crucial is to remember that the camshaft is just one link in a chain of components, so choose according to engine specification and advice from experts.

Published Dec 7th, 2015